Failed Oversight Follows Suburban Police Shootings

Review finds little evidence that suburban police departments second-guess their officers who fire weapons under questionable circumstances.

Police in suburban Cook County who shoot people under questionable circumstances do so with impunity, according to a review of every suburban police shooting over 13 years.

A Better Government Association/WBEZ examination of 113 police shootings in suburban Cook since 2005 found none in which police brass or law enforcement counterparts thought discipline or criminal charges were warranted against the officers involved.

At the same time, however, the investigation uncovered at least a half-dozen cases in which suburban officers saw careers flourish after being involved in a controversial shooting.

In 2012, Cicero officer Don Garrity shot and killed a suspected gang member who Garrity said pointed a gun at his partner. In a lawsuit, which Cicero settled for $3.5 million, the gang member’s family claimed he was unarmed and that police planted a gun near the body. Garrity was promoted from patrol officer to detective in the months following the shooting.

In 2007, Dwayne Wheeler, then a Maywood police sergeant, shot and killed a suspect through the window of a moving car, an action law enforcement experts say is both ill-advised and dangerous. Wheeler is now the police chief in a small central Illinois town.

In 2009, Riverdale officer Anthony Milton opened fire on an unarmed 23-year-old as he sat in the driver’s seat of a car outside his mother’s home. Reports suggest Milton, who approached the car because it was playing loud music, may have mistaken a screwdriver on the seat for a gun.

Milton was promoted to sergeant in February. Riverdale taxpayers wrote a check for $1.3 million to the family of the man Milton killed.

Police experts point to a number of reasons few officers face scrutiny over such actions — the potential for costly civil liability when police admit a mistake, the fraternal bond that inclines police to protect their own and a general reluctance to pass judgment on a fellow officer who acts in the heat of a moment.

“Unless it’s absolutely blatant or on video, they’re not going to upset the applecart,” said Gregory Kulis, a Chicago attorney who represents many families in police violence cases. “There’s the belief that they don’t have their officers’ back.”

Police departments in the suburbs of Cook County say they rely on the Illinois State Police Public Integrity Task Force to review police shootings. Illinois law requires a criminal investigation of police shootings be conducted by outside agencies.

But the BGA and WBEZ found those mandated probes rarely lead anywhere because they are limited in scope. They are designed only to determine if an officer committed a crime, not if he or she made mistakes, showed bad judgment or violated principles of sound policing.

Experts agreed that criminal investigations by themselves are insufficient, likely bypassing critical scrutiny of poor conduct that may not rise to a violation of law. Could the officer have used less lethal options to defuse the situation? Did he or she call for backup rather than charge into danger? Before firing, did the officer take note whether any innocent bystanders were nearby?

“Obtaining a criminal conviction in a police shooting case is extremely difficult. It just doesn’t happen very often,” said Samuel Walker, a professor emeritus at the University of Nebraska at Omaha and an expert on police accountability. “But what does exist is a failure of police officers to follow policy.

“If they’re only looking at whether there is a basis for a criminal indictment, they’re not doing a complete investigation,” Walker said.

This much is certain. When a suspect is shot by police in suburban Cook County the officer who pulled the trigger is never charged, and police departments involved rarely conduct more than a cursory investigation into policy violations if they look at all, the BGA/WBEZ investigation found.

‘There he was, bang!’

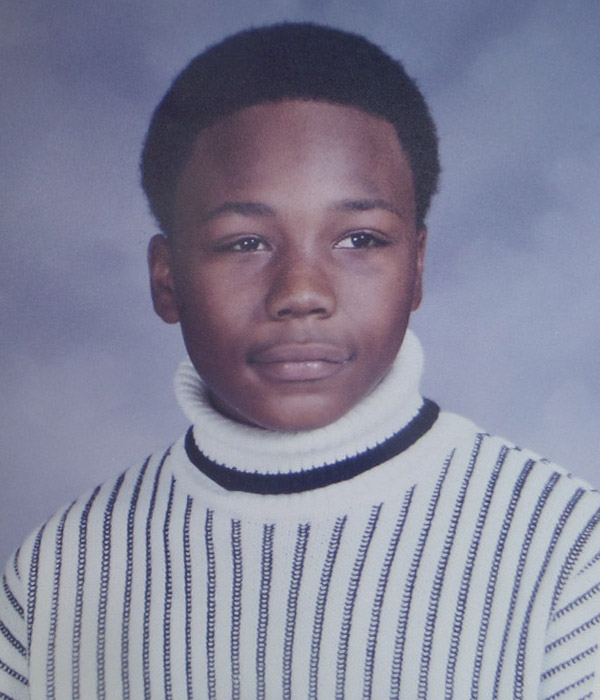

Anthony Milton was on patrol in south suburban Riverdale on Aug. 20, 2009 when he heard loud music coming from a parked car around lunchtime in a residential neighborhood.

Milton pulled his squad car in front of the 1993 Buick Regal. When 23-year-old Brandon Harper started to get out of the car, Milton drew his weapon and ordered Harper to stay seated, according to police reports.

Also in the car were two teens Harper was planning to drive to high school registration, his family said.

The only officer there, Milton ordered the three to raise their hands and place them on their faces as they sat in the car, which was steps away from the front door of a house where Harper’s mother lived.

Milton later told state police investigators he then saw Harper drop his right arm and noticed a “silver object” between Harper’s hip and the seat. He opened fire and shot Harper once in the chest, killing him.

Police later recovered a digital scale, a small bag of crack cocaine spattered with Harper’s blood and a flathead screwdriver in the front passenger’s seat. There was no weapon on anyone in the car, records show.

Harper died later in the hospital, nine days before the birth of his daughter, Simorah.

Suburban police shootings rarely gather much media attention, but the death of Harper was different. It prompted protests, television news coverage and demands for accountability. Harper’s family sued Riverdale, settling the case for $1.3 million. Among the beneficiaries was the daughter Harper never met.

“I had her two days after his funeral,” said Taneka Burks, Simorah’s mother, who ran out to Harper’s car after he was shot and had to be restrained by police. “It was good, and then it was still sad, because he had named her before she came but he just couldn’t get a chance to meet her.”

Milton, Riverdale police officials and Mayor Lawrence Jackson all declined to be interviewed.

State police found Milton had done nothing criminally wrong. The Cook County State’s Attorney’s office cleared him — as it has every officer in every suburban police shooting reviewed for this report.

The BGA/WBEZ found no evidence Riverdale conducted any follow-up examination of Milton’s actions, including why he used deadly force in a situation prompted by a report of loud music. Police records also do not explain why Milton failed to call for backup or why he opened fire on Harper with two minors so close.

One of the teens in the car that day was 17-year-old Christopher West-Umbra, sitting in the front passenger seat. “I guess he had put one hand down off his face, I guess he was trying to reach his pocket or something, and the police officer just shot him,” he said.

Also in the car was West-Umbra’s younger brother, Marcus. “It happened so fast it really is not even a story. We pulled up, he jumped out, there he was, bang! It just happened so fast," the younger brother said.

Milton was never disciplined or re-trained following the 2009 shooting, records show.

Officer ‘destroyed the crime scene’

The BGA/WBEZ investigation also found two cases, one in Maywood and the other in Cicero, where families of shooting victims claimed police dropped so-called “throw-down” guns near bodies to make it appear the victims had been armed.

Both incidents occurred in 2012 and police in both suburbs vigorously denied the allegations. No criminal charges have been filed against officers in either case.

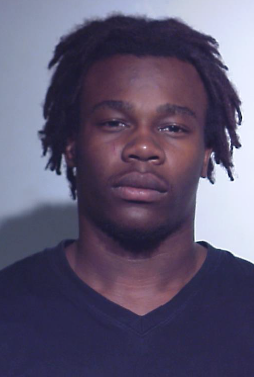

The Maywood shooting happened after police officers in that near west suburb rolled up on a group of men standing outside an apartment building around 4:30 p.m. on Nov. 8, 2012. One of them, 20-year-old Xavier McCord, ducked into the building and ran up the stairs.

Officer Michael Babicz, who later said in a deposition that McCord was doing nothing illegal when he first saw him, gave chase and yelled at several bystanders in the staircase to get out.

According to police reports, McCord was on the third floor when Babicz ordered him to stop. Babicz told state police investigators he opened fire when McCord pivoted toward him and pulled a gun. The fatal wound hit McCord in the chest.

As McCord slumped to the floor, he dropped the gun, which tumbled down the staircase to a second-floor landing, Babicz told investigators.

In the aftermath of the shooting, rookie officer Kyle Rice picked up the suspect’s gun and put it in the trunk of his squad car, reports say. He later told investigators he picked up the gun to secure the scene. Rice later returned the chrome Cobra .380 caliber handgun to the stairway where he claimed it had originally landed, according to police reports.

McCord’s family sued the Maywood police department, alleging McCord was unarmed when Babicz shot him and had never owned the gun that Rice moved that day. The lawsuit claimed Rice’s actions were an attempted coverup of a bad shooting.

Rice, who declined to comment for this story, told state police investigators he moved the weapon “for safety precautions” after hearing “unknown persons downstairs” saying "their shoo-tin (sic).” Rice was since promoted to detective in Maywood.

In a deposition connected to the McCord lawsuit, an Illinois State Police investigator said no fingerprints were found on the gun and there were no concerns about moving the gun because the area “needed to be secured.”

But Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart, when told details of the case, said Rice appeared to have “destroyed the crime scene.”

“At a minimum, you have to train people and you have to sit there and explain to them that you can't do that with the scene,” Dart said. “Say you were the most sincere, thoughtful person, you can’t do that.”

No administrative investigation was completed to determine whether Rice acted properly in moving the gun, or whether his actions should have at least forced him to undergo additional training, according to police records.

“It seems like something should be done,” said Steve Hinton, an attorney who represented McCord’s family in its lawsuit. “There should be some internal investigation, some training, some classes.”

Erica Williams, McCord’s mother, said she has unanswered questions.

“I still want to know today what reason they were bothering him,” Williams said. “What did he do?”

Maywood settled the lawsuit in January 2017 for $200,000.

Judge’s gun found at shooting

The Cicero case involved officer Don Garrity, who shot and killed Cesar Munive after he was seen fleeing a gang fight on a bicycle the night of July 5, 2012.

Garrity said while chasing Munive he saw the 22-year-old point a gun at another Cicero officer sitting in his squad car. Garrity told police investigators he ordered Munive to drop his weapon but then fired when Munive refused. Investigators found a .38 caliber weapon on the ground near the body.

Munive’s family sued the Town of Cicero, and as part of the case traced the gun to a Cook County judge, who said he had turned it over to Chicago police seven years earlier to be destroyed as part of a weapons buy-back program.

How that gun ended up by Munive’s body remains a mystery, but the details of its provenance came just weeks before Cicero agreed to a $3.5 million settlement in the family’s civil liability suit. Garrity’s lawyer, Craig Tobin, described his client as a hero and denied the gun was planted. He claimed Munive obtained it from another gang member.

Within a year after the shooting, Garrity was promoted from patrol officer to detective. He is now off the force and collecting a disability pension because of post-traumatic stress from the incident, according to Tobin.

Foxx: ‘Not in a position to fix it.’

In 2015, Illinois passed a law touted as a sweeping police reform that mandated independent oversight of police shootings for all agencies, increased police training and required collection of data on every police shooting in the state. The law set aside about $1 million each year intended for purchase of police body cameras.

Two years later, no body cameras have been purchased. Beyond an independent criminal review, the law requires no deeper procedural analysis of shootings, a longstanding requirement in larger departments such as Chicago.

State Sen. Kwame Raoul, D-Chicago, one of the bill’s sponsors and a current candidate for Illinois Attorney General, said it was a response to a “strong call from the public to do something and to get some transparency and accountability.” Sponsors, he said, had sought more provisions, including a requirement police be licensed by the state and that all officers be mandated to wear body cameras. The price tag prompted lawmakers to abandon the additional requirements, Raoul said.

State Rep. John Cabello, R-Machesney Park, a House sponsor of the bill who is also a Rockford police officer, remembered it differently. He said the final version was a “watered-down” compromise in which he worked to fend off the additional provisions sought by Raoul and others.

“It seems as though they were just trying to get anything passed to say ‘we did this,’” Cabello said of Raoul and others who wanted more.

On average, it takes the state police about 17 months to complete a criminal investigation of suburban Cook County police shootings.

In Chicago — like many other departments in larger cities — police shootings are investigated from all angles. The Civilian Office of Police Accountability, or COPA, is specifically set up to independently look for potential violations of policies and procedures by Chicago officers.

COPA recently replaced a predecessor agency beset by charges of ineffectiveness and a record of excusing questionable police shootings. When COPA investigates a shooting, basic information such as the date, location, and identities of the victim and police shooter are published on the agency’s website within weeks of a shooting. Later, when an investigation is completed, the findings are also posted online.

No such agency exists in the suburbs.

“If we could set up something like that, COPA for the suburban communities, it would be important,” said Cook County Commissioner Richard Boykin, an Oak Park Democrat. “It provides another layer of protection for the community for knowing accountability was in fact met.”

Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx would not discuss police procedures and policies, arguing that such issues are outside her role as the county’s chief law enforcement executive.

“For me I am not in a position to fix it,” she said, when told of the BGA/WBEZ findings. “My role looking at criminal charges is separate from that, administratively.”

Foxx was elected in 2016 promising to put greater emphasis on police accountability. “I can understand why millions of people who live outside the city of Chicago want to be able to make sure their departments are operating at their highest levels of professionalism and integrity,” she said.

That said, Foxx added, “I am not a policy maker in that space because that is not a space that I inhabit.”

Neither Foxx, nor her predecessor, Anita Alvarez, have filed criminal charges in any suburban Cook County police shooting, records show. In Foxx’s time in office, nine investigations of suburban police shootings have closed. Two others were still under investigation.

Richard Devine, the former Cook County State’s Attorney who helped oversee the formation of the state police Public Integrity Task Force, said police chiefs at smaller departments should never rely totally on a criminal investigation to decide whether officers acted appropriately.

“The investigation of whether criminal charges should be brought is dealing with a burden of proof that is at the highest,” Devine said. “If I were a police chief, I would not take the criminal investigation as the be-all and end-all of whether I would pursue disciplinary action against a person. In Chicago, it’s not uncommon at all, even if there are no criminal charges, to have some kind of discipline imposed.”

The BGA/WBEZ review found suburbs could rarely produce evidence of administrative investigations, let alone on the level of a COPA probe. In these examples, as well as the more limited ones conducted by other departments, officers were not disciplined or given training recommendations.

Take the case of Dwayne Wheeler, a former Maywood sergeant who fatally shot a 35-year-old drug suspect in the head in 2007 following an undercover sting in which a police informant bought $20 in cocaine and heroin.

As police converged on Fred Henderson’s car in a gas station parking lot that September night after the deal, police said he tried to drive away, striking a van and a squad car. Wheeler opened fire into the moving car, hitting Henderson in the left side of his head, and then ran away from the careening Lexus.

“We weren’t out there to hurt nobody, okay?” Wheeler said in a recent interview. “We were out there to rid the drugs off the streets of Maywood. We have done this hundreds of times without any incident.”

The village of Maywood agreed to pay Henderson’s family a $500,000 civil liability settlement. Wheeler’s decades-long police career has been dotted with problems.

In the months prior to the shooting, Wheeler was suspended for three days after engaging in a 100-mph chase over a traffic infraction in 2004. Two years after the shooting, he was fired from Maywood for not living within village limits.

He was detained for “suspicion of DUI” in Missouri the following year, and resigned from a police job in the Kane County community of Sleepy Hollow in July 2012, records show. That came days after a police officer in St. Charles, also in Kane County, discovered Wheeler asleep behind the wheel of a parked car. The records show he was suspected of intoxication with his hand laying on a .45 caliber handgun loaded with eight rounds of hollow point ammunition in the front passenger seat.

The officer who found Wheeler took his gun, and another officer gave Wheeler a ride home, letting him go without charges, records show.

“Pure and simple, this doesn’t rise to our expectations of how this case should be handled,” said St. Charles Deputy Police Chief David Kintz, who is now a chief at a community college. “There is no standing rule that just because he’s an officer he gets treated differently. Everyone who reads this will come to the same conclusion. The answer is he should have been arrested.”

Wheeler later got a job at the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office as an investigator. He now works as a police chief in Kincaid, a small town outside of Springfield, earning $47,000 a year.

“The thing is you make bad decisions in life, and I have, and I admit to it,” Wheeler said. “To me, it’s not corruption. I made a bad decision, alcohol was involved, and I moved on in my life from that.”

WBEZ criminal justice reporter Patrick Smith contributed to this report.