Nuclear Regulator Downplays Safety Warnings

A government body’s own staff is silenced in favor of arguments made by the power plant owners it oversees.

The federal agency responsible for safety at the nation’s 61 nuclear plants turns a deaf ear to warnings from its own experts about flooding, mechanical problems, power outages and other potential accidents that can lead to disaster, a Better Government Association investigation shows.

A review of thousands of pages of records and dozens of interviews during a months-long probe found:

-

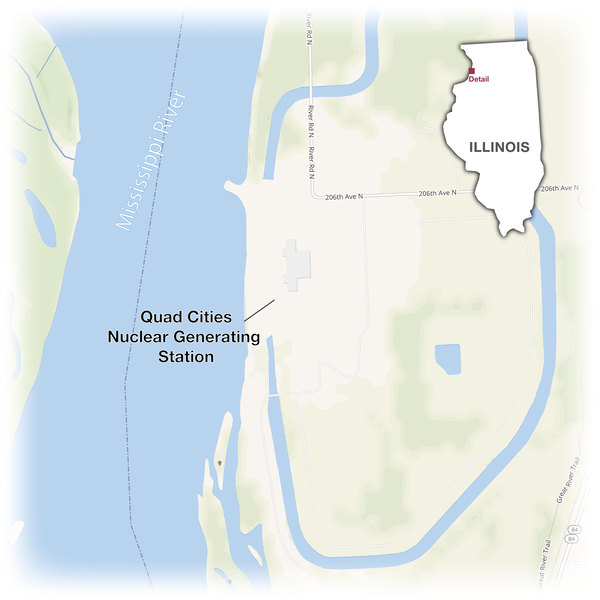

One-third of U.S. nuclear plants — including Chicago-based Exelon Corp.’s Dresden and Quad Cities sites in Illinois — have been deemed by agency experts to be vulnerable to big floods. Despite years of internal warnings and analysis, top brass at the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission have downplayed the threat and given nuclear operators leeway to take precautions its own experts say are inadequate.

-

Potentially dozens of nuclear plants across the country, including Exelon’s Braidwood and Byron sites in Illinois, are at risk of serious problems because of faulty internal valve systems needed to relieve water pressure in an accident, said Samuel Miranda, a retired NRC engineer who spent four decades in the nuclear industry, the last 14 years at the NRC.

A team of NRC experts ordered Exelon to prove its valve systems worked, but the company convinced the agency’s executive director to block the order in 2016.

-

Many U.S. nuclear plants have unreliable backup power systems, which could pose a danger of reactor core meltdowns, according to a team of NRC electrical engineers. They concluded the flaw was so serious that plants should be required to immediately fix it or shut down. The dire warning came in 2016, but the NRC agreed to requests from most operators to give them another two years to devise a fix.

In each example, technical experts say they were stifled by NRC higher ups when raising concerns about plant safeguards. In the high-stakes cases, NRC officials overruled staff recommendations and sided with nuclear operators in addressing the potential for plant catastrophes and potential harm to the public.

Officially, the agency encourages employees to speak up. But even internal NRC surveys point to a climate of fear and reticence among workers.

A report on a 2015 questionnaire of NRC employees stated most felt “if you disagree with your manager it can, and most likely will, affect your career path and advancement.” Nearly half surveyed concurred with the statement that “we too often sacrifice the quality of our work in order to: Satisfy a personal or political need.”

“It’s the NRC’s longstanding practice to consistently declare the plants are safe and to avoid directly answering any questions that might suggest otherwise,” said Lawrence Criscione, an NRC risk analyst from Springfield, Illinois, who sounded alarms about flooding risks at nuclear sites built long ago on flood plains.

Among such facilities are two in Illinois — Dresden near the confluence of the Kankakee and Des Plaines Rivers in Grundy County and the Quad Cities plant near the Mississippi River in Cordova.

Many of the plants now in operation were built in the 1960s and 1970s at a time when experts did not fully understand the potential for extreme floods and other natural disasters, Criscione said. More than half of U.S. nuclear power plants have reactors that are at or near their originally projected 40-year lifespans and almost all reactors in the U.S. have been granted extensions by the NRC to operate 20 years beyond that.

Records and interviews with current and former NRC employees reveal a pattern of top agency managers dismissing safety warnings from their technical experts rather than burden nuclear plant owners with costly fixes. Some of those interviewed said careers suffered even as potential threats to plants and the public were never fully addressed.

Top NRC executives declined interview requests, but the agency did respond in writing to questions from the BGA.

“All U.S. nuclear power plants have multiple appropriate procedures and resources in place to maintain key safety functions if severe events” occur, NRC spokeswoman Viktoria Mitlyng said in that statement. “These conclusions are based on extensive agency reviews and inspections.”

The nuclear industry, through its trade group and companies such as Exelon, downplay the seriousness of problems highlighted by NRC experts. Exelon and others in the industry have successfully batted down potential rules and regulations by pleading their cases to NRC’s top managers.

Exelon, the largest U.S. operator with 14 Midwest and East Coast nuclear plants, describes its relationship with the regulator as “unique and collaborative” and said the company simply follows NRC procedures to challenge agency decisions.

“Safety is the highest priority for both Exelon Generation and the NRC,” spokesman David Tillman said in a statement. “We are equally committed to protecting our people and our communities and to suggest otherwise is a disservice to the authority of the NRC and our shared commitment to public health and safety.”

The NRC and industry officials defend their safety record, pointing to a scorecard with no major nuclear accident in the U.S. since the 1979 meltdown at the Three Mile Island plant in Pennsylvania.

Many current and former technicians at the agency see it differently.

“The NRC is now working for Exelon,” charged Miranda.

The BGA identified several major safety concerns considered at the NRC since 2010. In each instance, the agency either blocked or scaled back fixes urged by its staff.

The problem, say people who conduct such reviews, is that the agency’s final rulings often don’t reflect the warnings from technical experts.

“Management tells you where they want the answer to go. If you push, you’re not going to get promoted again — there are other people who are willing to say it’s not a serious issue,” said Richard Perkins, one of Criscione’s NRC colleagues involved in exposing flooding concerns.

Perkins co-authored a 2011 report warning about nuclear plants at risk from dam failures. He said he sought Criscione’s help back then because he felt the NRC was withholding information from the public about the flooding threat.

The flood debate at the NRC has grown in intensity since 2011 when a tsunami triggered by a powerful earthquake flooded the oceanside Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in Japan, leading to a meltdown of three reactor cores that spread contamination for miles around and forced the evacuation of tens of thousands of people.

The Fukushima accident, among the worst in the history of nuclear power, prompted Congress to order the NRC to review flood safeguards at U.S. plants. An NRC task force then asked plants to submit plans to deal with floods more intense than those envisioned when many of the facilities were built decades ago. The agency, however, did not require operators to prove their plans would work.

One of those facilities was the Duke Energy Oconee Nuclear Station in South Carolina near Clemson University. It sits on a floodplain close to Lake Keowee, a large man-made reservoir and near the Jocassee Dam.

Even before Fukushima, NRC staff recommended that Oconee take precautions able to withstand waters that rose 19 feet above flood stage. But following the Japanese disaster, Duke proposed, and the NRC accepted, a plan sufficient to only protect against a 4.5-foot flood, according to written comments filed by NRC risk analyst Jeffrey Mitman in Criscione’s whistleblower case.

Chris Rimel, a spokesman for Duke, said that the NRC signed off on plant construction of a wall that would protect against a smaller flood, though he couldn’t be specific about flood height protection. “We mitigate as much as we can to avoid risk,” Rimel said.

Incensed by what he felt was bureaucratic indifference, Criscione aired his concerns about Oconee and other plants in a letter to members of Congress sent in 2012. That struck a nerve with his bosses.

Soon after, Criscione said, he was accused by the NRC inspector general of compromising confidential government information, interrogated by armed agents and saw his case referred to federal prosecutors.

They refused to pursue charges against Criscione, but the NRC continued its own investigation for months afterward, he said.

“It certainly was a stressful situation to be told by armed federal law enforcement officers that they were investigating you for a federal felony,” recalled Criscione, who said it was even tougher on his wife who was battling cancer at the time.

Criscione, who still works for the NRC, filed a federal whistleblower complaint challenging his treatment. He used the complaint to highlight NRC staff concerns that more than 20 plants are unprepared for major flooding from dam failures or rivers. He included Dresden and Quad Cities on that list.

As part of the NRC’s post-Fukushima reviews, the plans at Dresden and Quad Cities to handle extreme flooding were questioned by Mitman and other NRC experts. At a 2014 public hearing, they pointed to those facilities to highlight how older nuclear facilities lacked serious flood defense.

Exelon’s strategy for Dresden and Quad Cities was to not attempt to block flood waters but rather to allow them to enter the plants. Gas pumps would then be used to funnel in cooling river water to bathe reactors.

“The whole effort from the beginning was biased to not making the licensees make any major changes or improvements,” Criscione said in an interview. “The older plants deserved a different level of rigor.”

Exelon’s Tillman said in his emailed statement that both plants can “withstand the most severe local flood on record with margin to spare” and calls the NRC rare-flood models “an extremely unlikely, apocalyptic scenario.”

“Any assertion that Exelon’s nuclear facilities have outlived their ability to withstand flooding threats is inaccurate and misleading,” he added.

Criscione, however, points out that current licensing rules for nuclear plants would bar construction in the flood zones where Quad Cities and Dresden now sit.

Dresden began operation in 1960 and Quad Cities was licensed in 1972. Criscione said site selection for both facilities took place in an era when “our understanding of rare river floods was not what it is today,” Criscione said.

That understanding may still be evolving, as underscored by recent flooding in Houston that far exceeded prior worst-case scenarios. Benchmarks for catastrophic 100-year floods have changed as global warming scrambles weather patterns leading to more extreme storms.

The complaint brought by Criscione came to a resolution recently when the U.S. Office of Special Counsel, a government body that probes whistleblower complaints across many federal agencies, urged the NRC to “carefully consider” the expert warnings about flood precautions.

“Utilize their expertise,” the special counsel added.

NRC officials choose their words carefully when discussing the tension between keeping plants safe and saving nuclear operators money. But one former top official at the agency acknowledged in an interview that economics factors into its decision-making.

Jack R. Davis, who oversaw the NRC’s post-Fukushima flooding analysis, said it’s impossible to make plants 100 percent safe. “What I like to tell folks is safety resources are not unlimited — there’s a finite amount,” said Davis, a 20-year NRC veteran who left in 2016 to work for Entergy, an operator of several U.S. nuclear plants.

While still at the NRC, Davis was investigated by the agency’s inspector general for boasting on his LinkedIn page that he had saved the nuclear industry $1.6 billion while a regulator. That declaration, the IG found, broke no law yet “created an appearance of impropriety.”

A good government ‘win’

Miranda, the former NRC engineer, is continuing in his retirement to press his old employer over safety issues, including the fight over backup systems he started while still at the agency.

Nuclear plants create energy by boiling water into steam which turns turbines that produce electricity. Like a pressure cooker, steam buildup must be released through safety valves.

If primary valves malfunction, separate backup valves are needed to control water flow. Pressure relief valve failure contributed to the partial meltdown at Three Mile Island, Miranda explained.

Miranda said he was assigned in 2013 by the NRC to review a proposal by Exelon to increase power output at its Byron and Braidwood plants. He disputed Exelon’s contention that backup valves at the decades-old facilities would relieve water pressure in an accident.

Miranda and other NRC technical and legal staff studied the issue for two years and determined Exelon had not conducted required tests to prove the emergency valves would work if needed. Exelon was ordered to undergo the tests, but that was overturned in 2016 after the company appealed directly to Victor McCree, the NRC’s Executive Director for Operations.

The action was hailed as “a win for good government,” by the Nuclear Energy Institute, an industry trade group.

The price of major safety fixes can run into the tens of millions of dollars if multiple plants are affected, a significant cost even for an industry that claims at least $40 billion in annual revenue.

In resisting mandatory upgrades, nuclear operators often argue the cost isn’t justified when weighed against the low likelihood of an accident.

Economic interdependence between the industry and government dates back to the earliest days of nuclear power in the 1950s.

Federal officials concluded the potential costs of a serious accident could be so crushing that utilities would not take on the risk of building plants. The solution was the Price-Anderson Act, passed by Congress in 1957, a law that partially insulates the nuclear industry from liability in event of a catastrophe.

Mark Cooper, a Vermont-based economist and nuclear power critic, said the industry would be economically unviable without the special protections. “If Price-Anderson were repealed, and utilities faced full liabilities for accidents, the utilities would get out of business as fast as they could,” Cooper said.

NRC officials say safety and security of the plants are their top priorities and spokeswoman Mitlyng insists that the agency doesn’t side with plant owners to save the industry from costly upgrades to address safety concerns.

The reality is that the companies do influence NRC regulations as they fight back against proposed costly fixes, say current and former agency workers.

“The industry pushes back and says ‘listen, we’re not going along with this. It’s too expensive,’” said George Mulley, a former inspector general investigator at NRC who handled numerous cases involving plant safety over 26 years on the job.

As for the backup valves, Exelon said in a statement to the BGA that its own analysis proves existing equipment works sufficiently. In appealing the staff order for more testing, the company said it was abiding by the rules of the NRC and achieved an outcome that was a “textbook example of multiple nuclear power experts applying their technical knowledge to an issue.”

In a statement, the NRC defended the reversal, saying it determined the valve issue was of “minimal safety significance.”

By law, members of the public, including special interest groups and even NRC workers, have the right to petition the agency to reconsider policies it has put in place over a wide range of safety concerns, including emergency power systems and mechanical or structural issues. Between 2013 and 2016, there were 38 so-called public petitions filed with the NRC.

A recent internal audit at the NRC found that no safety fixes have been put into place in response to any of those petitions.

Miranda’s petition over the safety valve issue was rejected by the agency in June 2017. Also going nowhere were petitions from NRC electrical engineers over the backup power problems and another questioning the sufficiency of emergency backup power and safety at the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station operated by the Arizona Public Service Company in that state.

The backup power question was first raised by NRC electrical engineers after a problem was discovered with an emergency power system at Exelon’s Byron plant near Rockford. They also determined the problem at Byron was common to many other nuclear plants in the country.

Without backup power, plants might be unable to keep reactor cores cool to prevent a meltdown.

In 2016, seven of those engineers issued a public plea to the NRC seeking an immediate order for all plants to either fix the backup power deficiency or shut down.

“The Byron event identified a vulnerability,” the engineers wrote in their petition, warning power system failures “must not disable the safety functions of emergency core cooling and vital safety systems to protect the health and safety of the public.”

Exelon moved quickly to implement fixes at its plants. But other plant operators sought, and received, permission from the regulatory agency to have until late 2018 to devise voluntary solutions.

The NRC “should not impose any specific design requirements” for the plants, the Nuclear Energy Institute, an industry group, wrote to the agency in 2016. “The NRC should review each licensee’s approach for addressing” the issue.

The “voluntary initiative” to resolve the issue was deemed to be appropriate, Mitlyng told the BGA.