'Nobody Really Cares'

Employees at the nation’s nuclear power plants filed nearly 700 whistleblower complaints with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in recent years. It upheld zero.

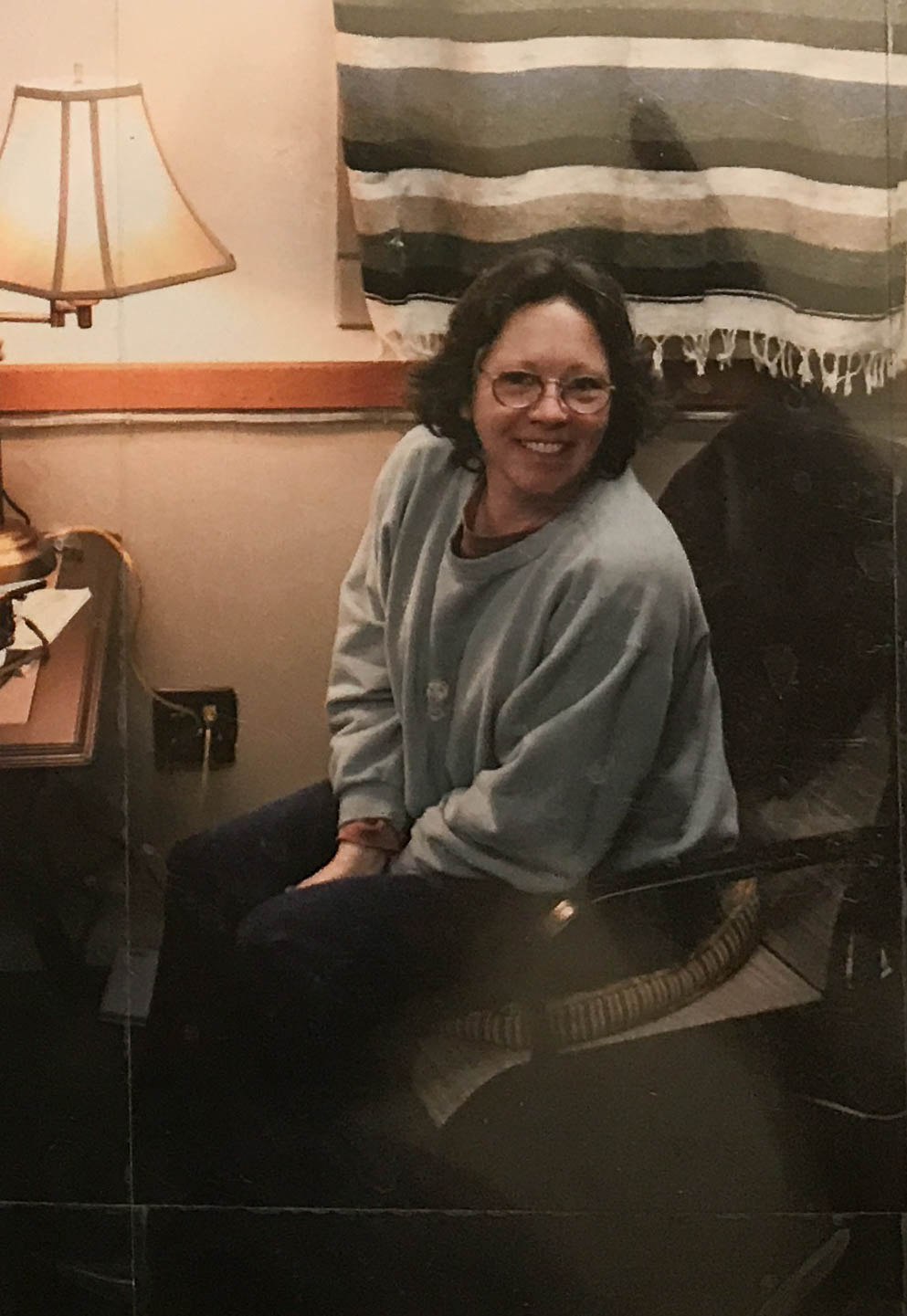

Marilyn Lingle, a nearly 30-year veteran of the nuclear generating industry, began a new job in 2010 helping dismantle Exelon’s long-shuttered Zion nuclear power plant. One of her assignments was to measure radiation on scrap metal before it was landfilled or recycled. Records show she did her work by-the-book, scouring each piece to ensure it wasn’t a public danger.

Yet Lingle’s methodical pace frustrated employees at ZionSolutions, a contractor hired by Exelon to decommission the plant site near the Wisconsin border, according to reports with the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. During the next few months she continued to have run-ins at the plant, and managers started to view her as “an annoyance and nuisance,” the records show.

Lingle’s bosses began faulting her job performance, accused her of disruptive behavior and issued reprimands. She was placed on suspension and sent to a counselor who found Lingle was suffering from stress brought on by “perceived threats, accusations and intimidation by management.”

Lingle filed a whistleblower complaint with the NRC that accused ZionSolutions of retaliation for airing safety concerns—one of hundreds of similar cases received by the agency in recent years that all ended the same, a Better Government Association analysis found.

Employees at the nation’s nuclear power plants filed 687 whistleblower complaints from 2010 to 2016, claiming retaliation for raising safety concerns, records show. The NRC only investigated about one-third of these allegations. It upheld zero.

The results underscore an entrenched pattern at the agency. The NRC encourages nuclear plant workers to speak out and says it relies on them to be its eyes and ears in the quest for safety in a nuclear generating industry that has little margin for error. But the agency’s record does little to support those claims.

Lingle never lived to see her complaint rejected. Two months after the NRC opened an investigation, she was found dead in her truck in her garage. The Lake County coroner’s office ruled that her death by carbon monoxide asphyxiation was an accident.

A year later, NRC investigators concluded that ZionSolutions managers had “greatly exaggerated” accusations against Lingle and her complaints of retaliation were valid. But the posthumous victory didn’t stick. After a final review with agency lawyers, the NRC rejected the findings and declined to act against ZionSolutions. Officials from ZionSolutions did not return repeated calls for comment.

Paul Blanch, himself a one-time plant whistleblower, nuclear engineer, and safety consultant for the nuclear industry, says such outcomes send a clear message summed up in gallows humor common among nuclear industry workers: NRC, they say, stands for “Nobody Really Cares.”

NRC spokeswoman Prema Chandrathil said the numbers don’t tell the whole story. The main reason no recent cases have concluded in a whistleblower’s favor, she said, is the threshold for accepting allegations is “very low” but the burden of proof needed to find wrongdoing by a nuclear operator is far higher.

“The NRC is focused on nuclear safety and enforcing its regulations, which prohibit discrimination against nuclear workers who raise nuclear safety concerns,” Chandrathil said in a written statement to the BGA.

Chandrathil added that more than a quarter of the discrimination cases received over the six-year period were never investigated because employees and companies reached private settlements before it got to that stage.

The NRC says the settlement process is beneficial to both sides but critics argue it is an easy way to silence whistleblowers and keep problems under wraps.

The BGA interviewed a dozen current and former nuclear plant workers across the country about their workplace cultures. Most described climates that emphasized silence over safety and said raising concerns that might lead to expensive repairs was considered a career killer.

Some employees still on the job declined to speak on the record, saying they feared repercussions and worried going to the NRC would accomplish nothing.

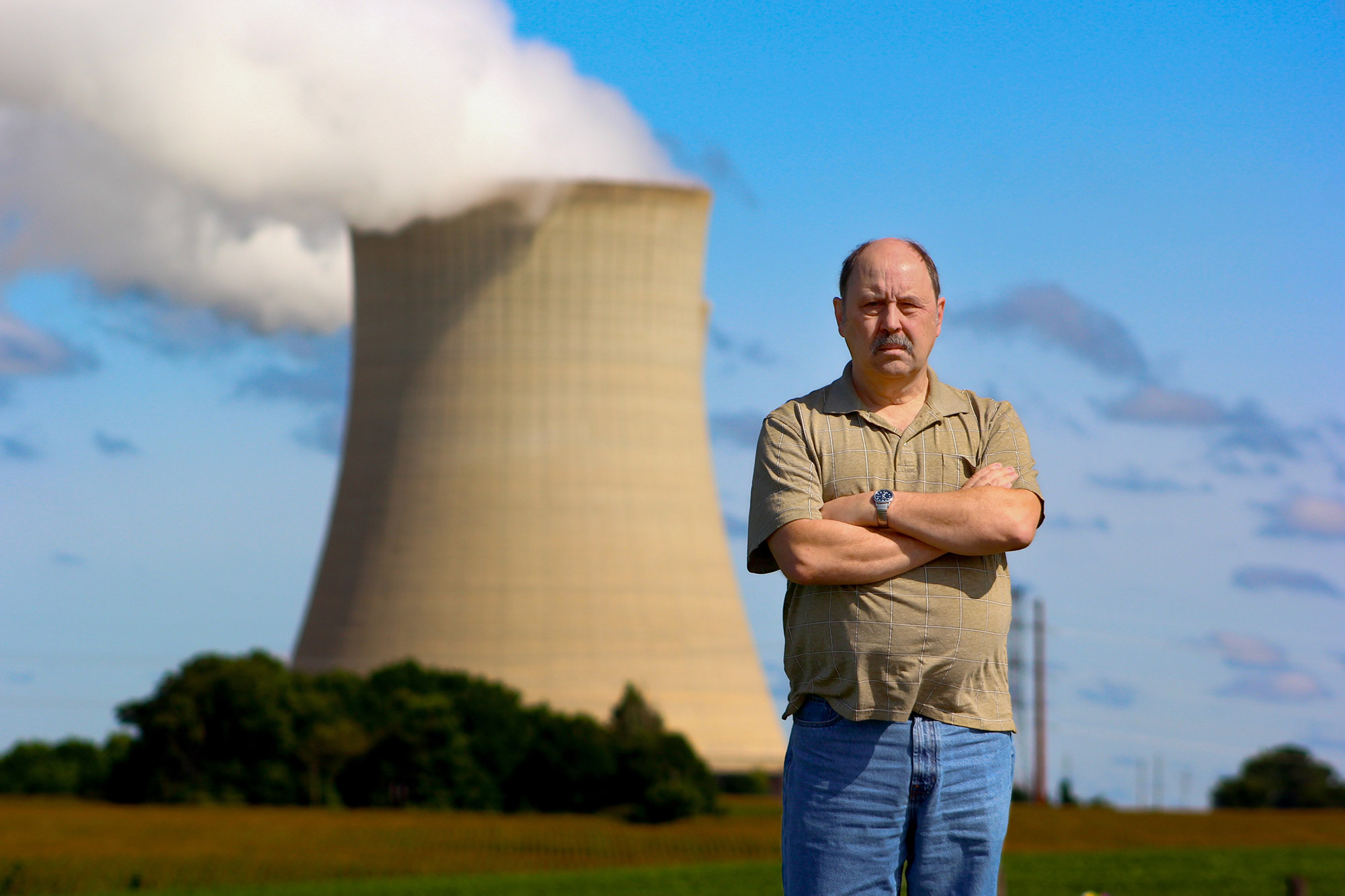

One longtime employee who did speak openly said employees have little faith the agency will thoroughly investigate concerns.

“They don’t find anything,” said Barry Quigley, a senior design engineering analyst who has worked at the Byron plant for 31 years. “It’s just not effective.”

Whistleblower cases are notoriously difficult to prove, regardless of the industry. The U.S. Department of Labor fielded more than 20,000 workplace complaints from whistleblowers over roughly the same six-year period and determined just 388, about 2 percent, had merit—a tiny fraction but still higher than results at the NRC.

In theory, nuclear power plant employees can file retaliation complaints with both the Labor Department and the NRC, but investigations at each agency are designed to serve different purposes.

The Labor Department has the authority to order employers to pay whistleblowers back pay or restore their jobs. The NRC lacks any such power to help workers personally and can only act to fix safety problems.

So a whistleblower complaint to the NRC is usually more selfless in intent, argued Billie Garde, a Washington, D.C., lawyer who has represented nuclear plant whistleblowers for more than three decades.

Among Garde’s clients is Chris Mikusko, who worked security at the Palisades nuclear plant near South Haven, Michigan, operated by Entergy Corporation. After 28 years at Palisades, he was laid off in 2013 for what plant managers termed a “restructuring,” but Mikusko claimed was in retaliation for reporting security-related problems, records show. One instance cited in Department of Labor reports show he complained that a supervisor asked another employee to fill in for an armed security guard position–a job the employee was not authorized to do–causing a security risk at the plant.

Mikusko filed whistleblower complaints with both the NRC and the labor department, and labor took his side. It ordered Entergy to restore his job, though Mikusko did not return after reaching a settlement with the company.

The NRC reached the opposite conclusion, deeming Mikusko’s retaliation claims unsubstantiated. Mikusko said he was shocked.

“I thought this is the kind of case that the NRC should be hanging their badges on,” Mikusko said. “We brought up concerns. We’re supposed to be protected.”

Chandrathil declined to comment on specifics of Mikusko’s case, but said the NRC is always rigorous in investigating retaliation claims.

The NRC, meanwhile, acknowledged a poor safety culture existed in the Palisades security department after Mikusko left. The agency surveyed plant employees and everyone from the security department who responded said they were not comfortable raising issues without fear of retaliation.

“After what happened to us, people were completely and genuinely afraid,” Mikusko said of his former co-workers. “After going through what we went through, I lost complete and utter faith in the NRC.”

In a prepared statement, Entergy spokeswoman Val Gent said Palisades plant management was proactive in responding to the NRC findings and had worked to establish “an unrelenting focus on safety.”

A perception that the NRC is indifferent to whistleblower allegations has long dogged the agency. In 1993, the NRC’s Office of the Inspector General conducted a study that found scant action taken when plant workers raise an alarm.

The study said the NRC had investigated just 44 of 609 retaliation complaints it received over a roughly five-year period. Only seven resulted in enforcement actions.

Whistleblowers, whose identities were withheld from the report, told the inspector general investigators they felt abandoned by the NRC and feared cooperating with the agency, or filing complaints with the labor department, would only lead to financial hardship and emotional pain, the report said.

The inspector general report outlined examples of intimidation that plant workers said they were forced to endure for speaking out. One said he was moved to a position with a higher level of radiation exposure after reporting problems.

Another recalled an incident when a co-worker pointed to a charred mannequin used in a firefighting exercise and said the whistleblower risked a similar fate if his behavior did not change. This whistleblower was later diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder attributed to workplace trauma, according to the report.

The U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works later held hearings on whistleblower treatment at the NRC. Then-Sen. Joseph Lieberman, a Connecticut Democrat, presided over the session and said he found the report disturbing.

“Serious problems of safety may exist today that we will not be warned about because workers may feel unprotected if they blow the whistle,” Lieberman warned at the time. “The law is not working if people cannot speak out when they see situations that they fear are dangerous because of greater fears of the legal, economic, or bureaucratic consequences.”

The inspector general at the time made several recommendations to improve the NRC’s handling of whistleblower complaints, though the agency did not formally adopt any of them.

Chandrathil, the NRC spokeswoman, said the agency embraced other changes, including in 2004 when it began offering whistleblowers the opportunity to privately mediate complaints with plant operators–a process the NRC billed as a path to speedy resolutions and enhanced plant safety.

As part of those confidential deals, employees often accept back pay if they had been suspended or fired but agree to quit or stop speaking about the safety concerns they had raised, according to Garde, the whistleblower attorney. While the NRC is still required to look into the underlying safety problems, those often aren’t taken as seriously without the whistleblowers pushing for change, she said.

“The NRC isn’t picking up the gauntlet of being an advocate for those issues,” Garde said. “What you’ve got is a system set up to basically pay them off, keep them quiet, settle the problem so it isn’t all over the newspaper or the TV.”